How long do cows wait to be milked in a free-flow automated milking system?

- October 26, 2023

When talking about long periods of standing, a common scenario that comes to mind is cows standing in a holding area, waiting to be milked in the parlor. On the flip side, we tend to assume that in automated milking systems (AMS), cows spend little to no time waiting to be milked as they have the freedom to choose when to access the milking robot without leaving their home pen. Whether in a parlor system or AMS, we know that long periods of standing are detrimental to cows’ health and comfort, increasing their chance to develop lameness and hoof lesions.

We explored cow behavior around milking time in a free-flow AMS. We conducted an observational study where we used video analysis from 40 cows over 2 days in 1 commercial free-flow AMS herd (Figure 1). We were curious to know how long cows wait to be milked; which factors have an impact on waiting time; and what choices cows make when they are unsuccessful in accessing the milking robot.

The study herd milked 180 Holstein cows with 3 robots and averaged 95lb of milk per cow per day over the prior 6 months. The study pen consisted of a mixed-parity group of 59 cows, and the free-flow milking robot was installed on the side of the barn, parallel to the pen. There was a fetch pen which remained open throughout the day so cows could enter voluntarily but was gated closed 3x/day when cows were fetched into the pen. The pen had a 3-row stall layout with 60 deep-bedded sand stalls and concrete flooring alleys.

How long do cows wait to be milked?

On average, cows visited the robot to wait to be milked 6 times per day, spent 15 min waiting per visit for a total waiting time of 1 hr and 30 mins per day. This daily waiting time is shorter than that reported for conventional parlor milked herds, but what was surprising was the large variation in waiting time among cows. Some cows were very efficient and only spent a total of 5 min per day waiting to be milked while other cows spent over 5 hours per day!

What were the differences between cows with short and long daily waiting times?

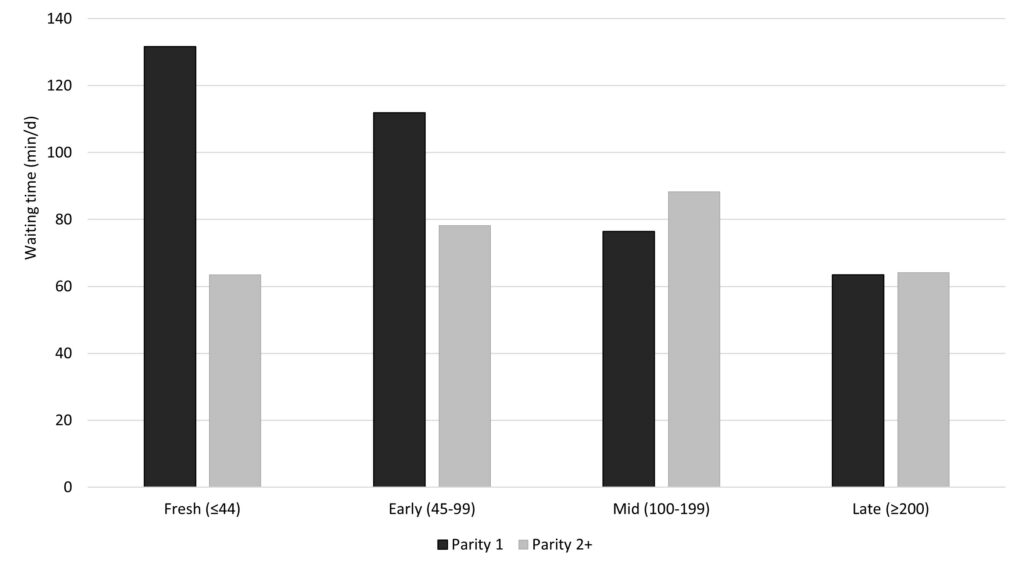

Parity, days in milk and their combination had an impact on daily waiting time (Figure 2). First parity cows in early lactation had more frequent and longer visits to the waiting area resulting in long waiting times (~2 h/d). But in late lactation, this behavior gradually became more like that of older cows, with fewer and shorter visits to the waiting area resulting in shorter waiting times (~ 1 h/d). It is likely that competition and ‘inexperience’ played a role in the long waiting time observed in first parity cows early in lactation. They often had to compete at the robot entryway with mature cows while trying to overcome the steep learning curve of using the robot.

Another factor that had an impact on daily waiting time was related to the voluntary and repeated use of the fetch pen throughout the day to access the robot. Cows that showed this behavior had on average 40 min longer waiting time and fewer visits to the waiting area compared with cows that rarely entered the fetch pen. Even among first parity cows, those that voluntarily and repeatedly used the fetch pen waited on average ~1 hr per day longer than those who did not.

If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again

If cows aren’t milked when they want to be, a free-flow traffic design gives them freedom to choose from a variety of alternative activities such as lying down, drinking or eating. So, what choices do cows make when they fail to access the robot? Most of the time, cows chose to move further from the robot and continued to stand idle in the alley or in a stall on the lookout for an opportunity to get milked. As time passed by, about 25% of the time, cows moved to the feedbunk or a water trough, but there was a much higher probability that cows would either continue standing in the alley, in a stall, or return to the waiting area. This suggests that the desire to be milked continues to influence behavioral decisions after a failed attempt to access the robot.

The longer cows wait to be milked, the less time they had to rest

On average, cows spent 10 hrs and 50 min per day lying down, with a wide variation from 5 to 16 hrs per day. Cows that had long waiting times (over 2 hrs per day) tended to spend an average of 1 hr and 40 min per day less lying compared to cows with shorter waiting times (less than 2 hrs per day).

Ways to mitigate competitive behavior by management and design

- A well-designed robot entry: cows that voluntarily used the fetch pen tended to wait longer because they were at a disadvantage when competing with cows outside of the fetch pen for access to the robot. Cows in the main waiting area exerted pressure over cows waiting in the fetch pen by forcing their way past the end of the swing gate. This battling of “who is the strongest cow pushing the swing gate” could be mitigated by having gating at the robot’s entryway that protects the neck and shoulder of the next cow in line (Figure 3). A design element of this kind would discourage dominant cows from displacing subordinate cows by limiting their interaction to the rear of the waiting cow.

- Robot exit area: after a successful milking, some cows exiting the robot displaced cows waiting in line to gain access to the robot. This displacement was sometimes a clear aggressive interaction from dominant cows but sometimes it was due to limited space in the robot area during periods of high robot visit frequency (“traffic jams”). An AMS layout where cows exit away from the robot entrance and are not able to interfere with cows waiting to access the robot could prevent this behavior.

- Stocking density: Maintaining an adequate stocking rate of cows per robot may lessen the dominance effect, decrease standing time, and decrease the impact of failed attempts to access the robot.

- Grouping strategies: Adoption of grouping strategies to reduce competitive behavior, especially towards primiparous cows, along with training heifers to use the robot before calving may help reduce waiting times.

FIGURES